In the 17th century the urang (people) of Bhumi Campa were in the midst of a dynamic period of transition. Having suffered the catastrophic defeat of the capital Vijaya in 1471, the Cam had moved their negara (capital) southward to Panduranga, situated in the heart of the modern Vietnamese province of Binh Thuan. With the conversion of the first Cam Ppo to Islam in 1607, and the tragic defeat of the epic devaraja (god-king) Ppo Rome during the Vietnamese annexation of Campa in 1651/3, it became clear that the Cam reliance on the moral authority of the Hindu-Buddhist divine universe was under threat. At sacred gatherings situated on the ritualistic combination of Cam animism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam the Cam kathar narrated the inner tensions of their communities in an attempt to preserve the unity of the Bhumi. Within this historical context two lyrical sung poems, or Ariyas: Ariya Cam-Bini and Ariya Bini-Cam, become particularly important in understanding the transition between a dominant authority of localized Hindu-Buddhist tradition, to the increasingly popular localizations of Islam. Thus, I suggest that scholars ought to begin to think of Cam identity through such a bifurcated lens, allowing for admission of previous scholarly assertions for Cam as being both Hindus and Muslims, as well as having a place among both Malayness and Vietnameseness.

Islam made its first appearances in Campa perhaps as early as the 9th or even 8th centuries in connection with globalized Arab dominated trading networks, which came to refer to Campa as Sanf. The Cam had already established long standing trading relationships with Sinitic peoples, which prized the Cam’s possession of luxury goods including; ivory, bees wax, tortoise shells, precious minerals, and aloeswood. The production of aloeswood not only drew the Cam would not only be an important aspect of Cam-Highland relations during the 17th century, but was also prized by the Arab traders, leading to an increased presence of Islamicized trading networks in the region, and the clear apparition of gravestones designating an established Islamicized population on the Cam coast in the 11th century. Although the Cam were a highly syncretized tradition, this new religion would, in its most strict orthodox understandings, create a threat to the Cam Hindu-Buddhist authority. Islam postulated that there was a divine essence which could be accessed though the moral leadership of the Imam, and thus undermined the divine apparition of the devaraja. Thus these two elements of Cam society were drawn into the conflict we see portrayed in the Ariyas: Cam-Bini and Bini-Cam.

Upon first examination Ariya Cam-Bini appears a simple Cam version of the age old tale of star-crossed lovers; a Cam Balamon (Hindu) man and a Cam Bini (Muslim) woman. Though the have sworn to keep their lives together, and even promised to unite eternally through the practice of Sati, they are ostracized by their community. Parents and neighbors appear as disapproving figures who visit extremely violent beatings and death threats upon the two lovers who then find themselves regulated to digging potatoes from the dirt to prevent starvation, and wandering in tattered clothes in the street. However, one crucial line in the poem hints at the greater implications of this narrative:

Cam Transliteration:

Kuw biai wok yuw ni baik ah

Ka than drei ribbah dom thun muni

Sa gah Cam sa gah Bini

Hake bhian yuw ni tat toy sa drei

Vietnamese Translation:

Ta bàn như vậy nhé

Vê thân phận mình khô mây năm nay

Một bên Cham, một bên Bàni

Đau thương như thê ni, trôi giạt như thê này

My English Translation:

We must share, we must converse about our destiny like this

Our situation is intertwined, it has been suffered for many years

One side is Cham, and the other is Bani

But we are not usually wandering, separately as boats on the water

In this sense we see that the two religious elements of Cam identity as manifest in the persona of the lovers. Additionally, the aquatic imagery of this passage demonstrates a well reviewed aspect of Cam identity as a Austronesian people that can be identities with a sense of Malayness. The image of watercraft becomes equally important in the Ariya Bini-Cam, where the Islamic lover is portrayed as originating from Mecca before appearing along the Cam coast from the ports by the Vietnamese names Phan Ri and Nha Trang. Here the image of wandering, separateness, and divergence are stressed again and again.

As Kieth Taylor (1999), Kenneth Hall (1999), William Southworth (2001), and Rie Nakamura (2003) have all shown, we must not imagine Cam polities as singular wholes, despite the tendency of many scholars, including experts of Campa, such as Po Dharma (1987) and P.B. LaFont (1991, 2007) to use the term negara Campa to refer to the whole. In fact, both Taylor and Hall argued for an essential Malayness to Cam geography and bureaucracy respectively. It is my suggestion that if scholars continue to conceive of the Cam in terms of their Malayness, that we also begin to think of the Cam polities metaphorically as perahu, expanding and contracting overtime, traveling up and down the coast of what is now Vietnam. In this understanding the Cam polities would be much more like the polities of other Malay states that dominated the Age of Commerce, particularly those of the Tanimbar Islands in Eastern Indonesia and the central Flores, and the smallest political unit in Tagolog Society, the barangay, or boat. It is in this understanding of an inherent connection to the greater Malay world, presented through the imagery in these two poems that allows us to better view the establishment of Cam communities in Ayudhya, Kampuchea, and Malaya/Kelantan. However, these connections no doubt warrant further research.

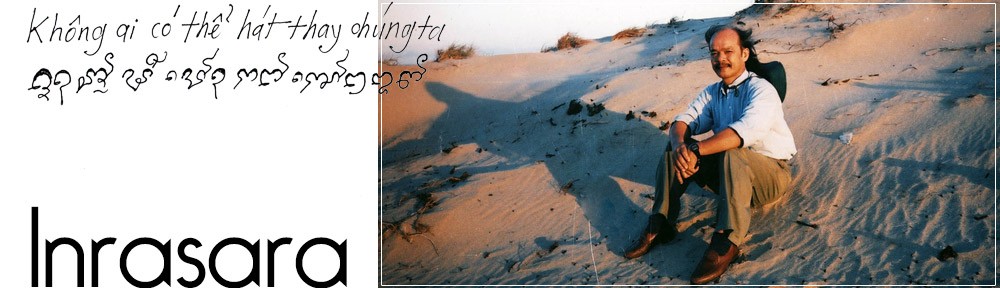

The relationship of the Cam to the greater construction of Vietnameseness is not a new concept. The celebrated works of Li Tana, Nguyen The Anh, and Phillip Taylor, among others, have demonstrated the role that Cam society played in the historical construction of contemporary Vietnamese identity. However, the works of Inrasara, who devoted his life study, analysis, and composition of what I might call Camness merits the particular attention of Vietnamese studies, in addition to the field of Asian Studies as a whole. Nevertheless, I would refine his application of Ariya Cam-Bini and Ariya Bini-Cam has been argued to apply to the later period of the 18th and 19th centuries, as well as more generally to the 15th through 19th centuries, as being particularly useful to the understanding of the historical conditions of Campa in the 17th century.

In the 17th century the Cam people witnessed the conquest of the territory of Phu Yen in 1611, followed quickly by the annexations of the negara of Kauthara in 1651/3, and Panduranga in 1692/3 and again in 1832/5. Meanwhile, after the conversion of the Khmer King Reameathipadei I to Islam, the Cam Muslim community in Cambodia gained prominence. Meanwhile, the Cam had clearly established trading connections dating from the 15th and 16th centuries in Kelantan, and a Cam community emerged in Ayudhya itself in 1692. Needless to say, the 17th marks a watershed moment in Cam history where the population is being pulled in two different directions, each marked with their own threats of annihilation and opportunities of contribution. In this examination the role of the Ariyas nuances the transition between a geographic understanding of sacred space dominated by Hindu-Buddhism, and one dominated by Islam.

In this essay I have argued for the particular importance of Ariya Cam-Bini and Ariya Bini-Cam in a nuanced understanding of the 17th century history of Campa. While previous scholarship has heralded the importance of the conversion the Cam people to Islam, much work still needs to be done to examine the history of this conversion and highlight the Cam interpretations of the narrative. In doing so it may be possible to not only argue for the importance of Camness as it relates to Malayness but also the construction of contemporary Vietnameseness as well. Recent contributions by the Cam poet/author Inrasara, who currently lives in Ho Chi Minh City are a much under celebrated aspect of this history. It is my suggestion that the increased study of the Ariyas particularly in English language scholarship and translation would be a great contribution to the fields of Vietnamese, Khmer, and Malay Studies, Asian Literature, and History, where the role of geography is no longer a force emphasizing the division between people, but rather a force that inherently establishes a fluidity in connectivity.

Thank yous:

This piece was created while on a FLAS (Foreign Language Area Studies Fellowship) for the study of the Vietnamese Language. In the composition of this piece I am greatly indebted to my advisor Aj. Thongchai Winichakul for his encouragement and criticism.In Insara’s translation method he has taken the Cam trường ca and with a two step process created both a dịch nghĩa, being a literal translation, and a “dịch thơ” being a poetic translation. In order to attempt to bring this beautiful text fully and completely into the English language, I translated directly from the “dịch nghĩa”, in order to best ascertain the meaning by my understanding. Often, words or phrases that are left in parenthesis are either added for the sake of fluency, or retained in their original forms. For assisting me in this project I am greatly indebted to my Vietnamese teachers; Thầy Bắc for his renaissance teaching approach, Thầy Hoa for his assistance with my understanding of tone and rhythm, Cô Thuyên for her motivational conversations, and Cô Hồng Thi Đình for all her patience, and willingness to see this part of what proposes to be an ongoing project to fruition.

*

(1) For the conception of Bhumi Campa see: Schweyer, Anne-Valérie. Le Viêtnam Ancien. Paris : Les Belles lettres, 2005. pp 60-1. For the conversion of the first king see: Howard, Michael C. “The Cham of Vietnam and their Textiles” Arts of Asia. Vol. 35. No. 2, 2005. p 124. For the narrative of Po Rome see: Taylor, Nora. “The Sculpture of the Cham King Po Rame of Panduranga: A Discussion of the Historical and Religious Significance of the Post-Mortem Deification of Kings in the Art of Champa”, A Paper for Asian Studies 601 Under Professor Keith Taylor, December, 1989. pp 11-13

(2) For the introduction of Islam into Campa see: Setudeh-Nejad, Shehab. “The Cham Muslims of Southeast-Asia: A Historical Note” in Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. Vol. 22. No. 2, 2002. pp 451-454 and Reid, Anthony. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce: Volume Two Expansion and Crisis. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. 1993. pp 132-4, 150-7. For conceptions of the nature of Cam trade and the importance of Aloeswood see: Southworth, William. “The origins of Campa in Central Vietnam: a preliminary review.” from PhD Thesis in Archeology: In Two Parts, SOAS, London. 2001. p 39, and Tana, Li. Nguyễn Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Cornell University Press. 1998. p 79.

(3) For the Inrasara’s production of Ariya Cam-Bini see: Inrasara (Phú Trạm). Ariya Cam: Trường ca Chăm. TP Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà Xuất Bản Văn Nghệ. 2005.

(4) For Inrasara’s analysis of Ariya Bini-Cam see: Inrasara (Phú Trạm). Văn Học Chăm I. Nxb. VHDT, H. 1994. pp 161-174

(5) Andaya, Barbara. “Oceans Unbounded,” Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 65. No. 4, Nov 2006. p 678.

(6) For Khmer connections see: Kersten, Carool. Cambodia’s Muslim King: Khmer and Dutch Sources on the Conversion of Reameathipadei I, 1642-1658. Journal of Southeast-Asian Studies. 37 (1) pp 1-22. February 2006. For Malay connections see: Le Campa et Le Monde Malais: Actes de la Conférence Internationale sur le Campa et le Monde Malais. Organisée A l’Université de Californie, Berkeley. 30-31 Août 1990. Paris: Les Indes Savantes, 1991. For connections to Ayudhya see: Actes du Séminaire sur le Campa: Organise a L’Universite de Copenhague Le 23 Mai 1988. Paris: ACHCPI, 1988.

Bibliography:

Andaya, Barbara. “Oceans Unbounded,” Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 65. No. 4, Nov 2006.

Conference Volume. Actes du Séminaire sur le Campa: Organise a L’Universite de Copenhague Le 23 Mai 1988. Paris: ACHCPI, 1988.

Conference Volume. Le Campa et Le Monde Malais: Actes de la Conférence Internationale sur le Campa et le Monde Malais. Organisée A l’Université de Californie, Berkeley. 30-31 Août 1990. Paris: Les Indes Savantes, 1991.

Howard, Michael C. “The Cham of Vietnam and their Textiles” Arts of Asia. Vol. 35. No. 2, 2005.

Inrasara (Phú Trạm). Văn Học Chăm I. Nxb. VHDT, H. 1994.

Inrasara (Phú Tram). Ariya Cam: Trường ca Chăm. TP Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà Xuất Bản Văn Nghệ. 2005.

Kersten, Carool. Cambodia’s Muslim King: Khmer and Dutch Sources on the Conversion of Reameathipadei I, 1642-1658. Journal of Southeast-Asian Studies. 37 (1) pp 1-22. February 2006.

Reid, Anthony. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce: Volume Two Expansion and Crisis. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. 1993.

Schweyer, Anne-Valérie. Le Viêtnam Ancien. Paris : Les Belles lettres, 2005.

Setudeh-Nejad, Shehab. “The Cham Muslims of Southeast-Asia: A Historical Note” in Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. Vol. 22. No. 2, 2002.

Southworth, William. “The origins of Campa in Central Vietnam: a preliminary review.” from PhD Thesis in Archeology: In Two Parts, SOAS, London. 2001.

Tana, Li. Nguyễn Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Cornell University Press. 1998.

Taylor, Nora. “The Sculpture of the Cham King Po Rame of Panduranga: A Discussion of the Historical and Religious Significance of the Post-Mortem Deification of Kings in the Art of Champa”, A Paper for Asian Studies 601 Under Professor Keith Taylor, December, 1989.

*

William Brokaw Noseworthy

University of Wisconsin Madison

241 Langdon St.

Madison, WI, 53703

noseworthy@wisc.edu

(802) 989-2870