Translated into English by A. G. Sachner

Explicated by Dr Ramesh Mukhopadhyaya

“… the speaker has verdure aglow within. Rivers of love flow in his heart unimpeded. May the tribe of such speakers multiply. The externalization of their inner world might bring back the lost Eden upon earth. The speaker becomes nostalgic. The lullaby becomes suddenly sad. The temple suddenly deserted…”

… thi sĩ có cây xanh rực sáng trong ông. Dòng nước tình yêu trong trái tim ông không bị ngăn trở. Dân tộc ông như được sinh sôi. Sự biểu lộ tình cảm của thế giới nội tâm họ có thể mang thiên đường đã mất trở lại mặt đất. Thi sĩ trở thành một hoài niệm. Các bài hát ru chợt buồn. Tháp Chàm qua đó, đột nhiên hoang hóa trở lại. Tất cả trở lại bản thể uyên nguyên…”

ANALYSIS

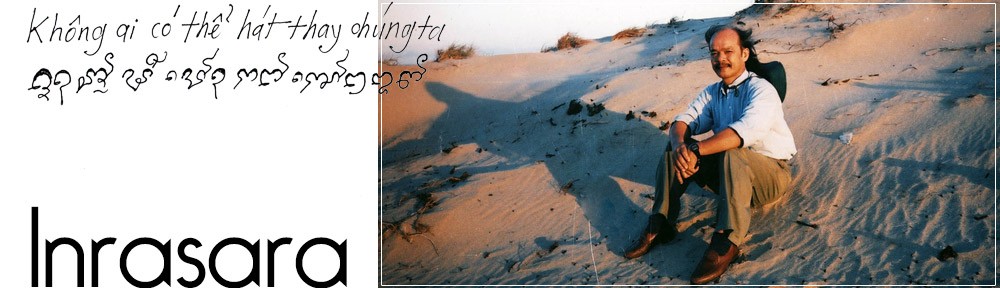

This is an autobiographical poem. The speaker here speaks in the first person. The speaker introduces himself as a child of the wind wandering through the fields of the narrow central region, a child of the fiery sun, four seasons of dry cold white sands, a child of the open sea filled with roaring storms and of the pale green sleepless eyes of the Cham temple. That is the first stanza of the poem almost ad verbatim.

The wind wandering through the fields of the narrow region gives us a sense of touch. The fiery sun and the four seasons of dry cold white sands also give us the sense of touch. Our feet feel the cold sands. Our eyes see the white sands. Our skin feels the hot sun. Our eyes see the hot sun. We can hear the roaring storms and descry the seas tossed by it.

Thus the first four lines of the poem engross our eyes ears and our sense of touch. They speak of a landscape where the wings are as it were howling at all hours.

Restlessness rules all over. The restless landscape is juxtaposed with the sleepless eyes of the Cham temple. That is, the Cham temple stands there tranquil looking on the restlessness of nature. While the seas are ever restless the Cham temple is ever in its tranquility. Does not the Cham temple symbolize a mind ever tranquil and perennial observing the phenomenal world where restlessness is the rule? The Cham temple looks upon the world with sleepless eyes. But on another level does not the poet say that he is the child of wind fire water and the earth the four elements that constitute the world? His mind is however one with the primordial mind that looks upon the restless world. On another level the Cham people were b rave sea voyagers who dared the wild seas in ancient times. It were they who founded the grand kingdom of Champa. Does not the speaker hark back to his ancient past? He remembers that he is the child of maritime adventurers in his unconscious mind.

The second stanza of the poem wistfully looks back to the indeterminate past. How is a child socialized? The speaker says that as a child he was fed with the milk of the sad folk songs. When a child he heard from his father the heroic poem Glang Anak his grandfather fed him with the foggy moon of legends. In fact a child is not brought up with nutritious food alone. And it is the stories that a child voraciously eats and the speaker tells us how he was nurtured by the stories. Every rift of the poem is loaded with rich ore. Such phrases as – the sinewy arms of Glang Anak, the foggy moon of legends are time and again .They present before us the picture of a child surrounded by grandpa and mother. Lights from the father’s eyes fall on him. But this is a picture of a family, of a people who are wont to cast a longing lingering look back to their glorious past. Right now they are sans the glory which they were wont to enjoy earlier. It speaks of a people with lost glory and lasting pain. It was in a village that the speaker spent his childhood. What was the village like? Well the speaker says that the village fed him with the shadow of kites, souls of crickets and the sounds of buffalo bells. Such portrayals of a village far from the madding crowds in noble strife is archetypal.

To any Indian reader this portrayal of a Cham village reminds of the countless villages of India itself. India by the by is still a network of villages even in the twenty first century. But this is not all. The shadow of kites the souls of cricket the sounds of buffalo bells seem to correspond to the sad folk song, arms of Glang Anak and the foggy moon of legends. In the moonlight we could descry everything but in the foggy moon whatever we see is hazy bright. Things no longer remain discrete there. The village in the shadow of the kites is as distant and as wistful as the sad folk songs that tell us of homely joys and sorrows or else that alludes to some battle lost and won.

The idyllic imagery of childhood is all of a sudden shattered with his growing up. In his adolescence the speaker confronted the world and the war. Those who know Vietnam of today know full well how the country was confronted with war. It was like the sea ravaged by the storm. And every inhabitant of the country had to face the ravages of war .With the speaker the war was without and the war was within. On the physical level, the speaker strived for food and clothing. On the mental level, he had to encounter clashing philosophies such as existentialism of Sartre and Kierkegaard and phenomenology of Husserl. But they be- speak of language game. The speaker was carried off by the flows of language and lost his stay. Does not the speaker thereby suggest the helplessness of the Cham people who have lost their ancient glory and state. But finally the speaker was plunged into the valley of love. Let the philosophers continue their dispute which has no ending love is the only philosophy and a feeling that wields the opposites.

Plunged in love the speaker dropped the world and lost his self. Here is as it were a sudden reversal of events. We expected that the speaker would find a stay in love. But the opposite took place. The speaker lost the rhythm of the country dance and the folk songs. His heart was blinded. He was like a person shunned falling into middle of a defoliated forest. This is a wonderful pen picture. We can visualize a young man forlorn plunged in- to the middle of a forest that had shed its leaves. This is the climax of a narrative.

In the fifth stanza the speaker says that flung into the defoliated forest he forced his head up and crawled out. This puts in our mind the portrait of a soldier crawling out of forest. This was on the physical plane. On the mental plane, the poet stretched himself from the pit of the past. The speaker / the poet likened the wounded person, searching for an exit from the ruins of a city. This imagery applies to the Cham people also who were in search of an identity. The imagery speaks of Vietnam shaking off the hang over of war. The speaker rediscovered himself, or retrieved his lost self finding the sunlight of the native country. Patriotism and love for one’s people and one’s motherland constitute one’s self.

Thus here is a story of paradise lost and paradise regained. Now that the speaker has found his own self once again, he is green. A fresh zest for life charges him. The speaker is green again even though the forest is burnt. Inside him there is a flow even though the river has died. This imagery might speak of the war ravaged Vietnam where forests and rivers became preys to napalm bombs. Or else, this is the portrait of the world today where urbanization robs the earth of its forests and where dammed rivers have lost their flow. But the speaker has verdure aglow within. Rivers of love flow in his heart unimpeded. May the tribe of such speakers multiply. The externalization of their inner world might bring back the lost Eden upon earth. The speaker becomes nostalgic. The lullaby becomes suddenly sad. The temple suddenly deserted.

The people of Vietnam particularly the Cham people are fond of ancestor worship. The poem ends with- Mothers distant voice soothes into an everlasting slumber. The poem seems to counterpoise Coleridge’s Kubla Khan. In Coleridge, Kubla Khan heard the voice of ancestors prophesying war. Here the distant voice of the mother soothes the speaker into an everlasting slumber. All passions spent there is a calm of the mind.

The poem is archetypal in so far as it describes the course of the life of every man in four stages – childhood adolescence youth and old age

*

ĐỨA CON CỦA ĐẤT

Tôi,

đứa con của ngọn gió lang thang cánh đồng miền Trung nhỏ hẹp

đứa con của nắng lửa bốn mùa cát trắng hanh hao

đứa con của biển khơi trùng trùng bão thét

và của đôi mắt tháp Chàm mất ngủ xanh xao.

Mẹ nuôi tôi bằng bầu sữa ca dao buồn

cha nuôi tôi bằng cánh tay săn Glang Anak

ông nuôi tôi bằng vầng trăng sương mù truyền thuyết

plây nuôi tôi bằng bóng diều, hồn dế, tiếng mõ trâu.

Lớn lên,

tôi đụng đầu với chiến tranh

tôi cụng đầu với cơm áo, hiện sinh, hiện tượng

tôi chới với giữa dòng ngữ ngôn hoang đãng

rồi cuộn chìm trong thung lũng tình yêu em.

Tôi đánh rơi thế giới và tôi lạc mất tôi

tôi lạc mất điệu đwa buk, câu ariya, bụi ớt

trái tim đui

tôi như người bị vứt

rớt giữa cánh rừng hoang trụi lá mùa xanh.

Rồi tôi ngóc đầu dậy và tôi trườn lên

rồi tôi rướn mình khỏi hố hang quá khứ

như kẻ bị thương mò tìm lối ra khỏi đống tan hoang thành phố

tôi tìm lại tôi

tìm thấy nắng quê hương!

Lại xanh trong tôi – dù rừng đã cháy

lại chảy trong tôi – dù sông đã chết

chợt hanh lại cát – chợt buồn lại ru

chợt duyên lại em – chợt hoang lại tháp

Giọng mẹ xa vời dỗ giấc thiên thu.

CHILD OF THE EARTH

I am

a child of the wind wandering through the fields of the narrow Central Region

a child of the fiery sun, four seasons of dry cold white sands

a child of the open sea filled with roaring storms

and of the pale green sleepless eyes of the Cham temple.

Mother feeds me with the milk of sad folksongs

father feeds me with the sinewy arms of Glang Anak

grandpa feeds me with the foggy moon of legends

the palei feeds me with the shadows of kites, the souls of crickets, the sounds of buffalo-bells.

Growing up

I confronted the war

I clashed with food and clothing, existentialism, phenomenology

I floundered in the flows of language gone astray

then was submerged in the valley of your love.

I dropped the world and lost my self

I lost the rhythm of duabuk, the lines of ariya, and the chili-pepper bush

with my blind heart

I was like a person shunned

falling into the middle of a defoliated forest.

Then I forced my head up and crawled out

then I stretched myself from the pit of the past

like a wounded person searching for an exit from the ruins of a city

I sought my self

finding the sunlight of native country!

Inside me green again – even though the forest has burned

inside me flowing again – even though the river has died

the sand suddenly parched – the lullaby suddenly sad

you are suddenly graceful – the temple suddenly deserted

Mother’s distant voice soothes into an everlasting slumber.

*

Đây là một bài thơ tự thuật, biểu hiện ở ngôi thứ nhất. Thi sĩ giới thiệu mình là đứa con của gió lang thang qua cánh đồng miền Trung nhỏ hẹp, đứa con của mặt trời cháy lửa, bốn mùa cát trắng hanh khô, đứa con của biển khơi bão tố ầm ầm và là đứa con của “đôi mắt tháp Chàm mất ngủ xanh xao”. Đó là phân khúc đầu tiên của bài được diễn nôm gần như là nguyên văn.

Con gió lang thang qua cánh đồng nhỏ hẹp như có thể sờ mó được. Mặt trời rực lửa và bốn mùa hanh cát trắng cũng cho ta cảm nhậntương tự. Bàn chân ta cảm nghe cát lạnh. Đôi mắt ta nhìn thấy bãi cát trắng. Làn da ta cảm giác cái nắng nóng của mặt trời. Tai ta có thể nghe thấy những cơn bão ầm ầm và cảm nhận biển vỗ sóngở phía xa xa.

Như vậy, bốn dòng đầu tiên của bài thơ đã thâu tóm toàn bộ giác quan ta, để ta nhìn, nghe, sờ mó. Thơ cho ta cảm nhận một vùng đất nơi những đôi cánh của giác quan luôn bay bổng.

Sự lo lắng bồn chồn ngự trị tất cả. Các cảnh quan đầy bất trắc được đặt cạnh nhau trước đôi mắt mất ngủ của tháp Chàm. Tháp Chàm lặng lẽ đứng nhìn vào nỗi bất trắc của thiên nhiên. Trong khi biển muôn đời bồn chồn thì tháp Chàm vẫn mãi mãi an định. Chẳng phải tháp Chàm tượng trưng cho một tâm trí an tịnh để, ngày qua ngày ngắm nhìn cái thế giới hiện tượng ở đó sự bất an trở thành quy luật muôn đời? Tháp Chàm như thể nhìn thế giới với đôi mắt mất ngủ. Tuy nhiên, ở một cấp độ khác, chẳngphải nhà thơ cho rằng ông là đứa con của nước, lửa, gió, và đất – là bốn yếu tố cấu thành nên thế giới sao? Tuy nhiên, tâm trí của nhà thơđã làm một với tâm nguyên ủy để nhìn sâu vào thế giới bất trắc. Ở bình diện khác, người Chăm nổi tiếng là dân tộc dũng cảm thám hiểm biển khơi nhiều hoang đảo vào thời cổ đại. Một vương quốc Champa hùng mạnh được thành lập ở đó. Và chẳng phải kẻ phát ngôn vừa nghe vẳng lại quá khứ xa xưa của mình? Trong sâu thẳm tiềm thức, ông nhớ mình là đứa con của nhà thám hiểm hàng hải.

Ở phân khúc thứ hai, thi sĩ nhìn lại quá khứ bất định bằng một giọng buồn. Thế nào là đứa con thích nghi với xã hội? Thi sĩ cho rằng đó là một đứa con được nuôi bằng “bầu sữa dân ca buồn”, bằng lời thơ Glang Anaktừ người cha, bằng “vầng trăng sương mù truyền thuyết” từ người ông. Trong thực tế đời sống, một đứa trẻ không được nuôi dưỡng bằng thức ăn biệt lạ như thế. Nhưng đó là những câu chuyện mà một đứa trẻ từng ăn ngấu nghiến, và thi sĩcho ta biết ông đã được nuôi dưỡng bởi những thứ đó như thế nào. Mỗi kẽ nứt của bài thơ đều được nạp bằng quặng giàu. Các cụm từ như –“cánh tay săn Glang Anak”, “vầng trăng sương mù truyền thuyết”mang ý nghĩa thời tính và lần nữa lặp lại. Thơ bày ra trước ta hình ảnh của một đứa trẻ được bao bọc bởi người ông và bà mẹ. Ông thu nhận ánh nhìn của cha. Nhưng đây là hình ảnh của một gia đình, hình ảnh một dân tộc ở đó họ quen phóng thả cái nhìn vào nỗi khao khát kéo dài về quá khứ huy hoàng của mình. Ngay bây giờ họ ca hát về niềm vinh quang mà họ quen thưởng thức trước đó. Thơ nói về kẻ đánh mất sự vinh quang và cưu mang niềm đau liên lỉ. Là chuyện ngôi làng thi sĩ sống qua tuổi thơ của mình. Làng kia bao gồm những gì? Ông viết: làng cho ông ăn cái bóng của diều, linh hồn của dế, và âm thanh tiếng mõ trâu. Miêu tả một ngôi làng tách rời khỏi cái chungđầy cá biệtnhư thế trong niềm xung đột cao quý là rất điển hình.

Nếu để cho bất cứ độc giả Ấn Độ nào biết đến miêu tả này của một làng Chăm chắc chắn họ sẽ liên tưởng đến vô số làng Ấn của chính họ. Ấn Độ vẫn còn tồn tại một mạng lưới làng mạc cả trong hai mươi thế kỷ đầu tiên. Nhưng đây không phải là tất cả. “Bóng diều, hồn dế, tiếng mõ trâu” dường như tương ứng với “dân ca buồn”. Cả “cánh tay săn Glang Anak” và “vầng trăng sương mù truyền thuyết” cũng thế. Dưới ánh trăng, ta có thể cảm nhận mọi thứ từ xa, nhưng quavầng trăng sương mù thì bất cứ điều gì ta thấy là sáng mờ. Những điều không tồn tại nữa vẫn có mặt ở đó. Ngôi làng với bóng diều thì vời xa và cảm nghe tiếc nuối như những bài dân ca buồn kể cho ta về niềm vui và nỗi buồn giản dị, hoặc giả chúng ám chỉ những trận chiến mất và được.

Những hình ảnh bình dị của thời thơ ấu bị phá vỡ đột ngột cùng lúc với sự trưởng thành của ông. Ở tuổi thanh niên, nhà thơ đối mặt với thế giới và chiến tranh. Ai từng hiểu Việt Nam ngày nay đều biết rõ đất nước đã phải trải qua chiến tranh như thế nào. Hệt biển cả bị tàn phá bởi trận bão. Và mỗi con dân của đất nước kia đã phải đối mặt với sự tàn phá của bom đạn .Với thi sĩ, cuộc chiến diễn ra trong tâm hồn ông. Trên bình diện vật lý, thi sĩ phấn đấu tìm kế sinh nhai. Ở cấp độ tinh thần, ông đã phải đụng đầu với các hệ tư tưởng: như hiện sinh của Sartre và Kierkegaard và hiện tượng học của Husserl. Trong lúc các tư tưởng gia kia được tham gia vào trò chơi ngôn ngữ, thì thi sĩ chúng ta bị cuộn xoáy bởi các dòng chảy của ngôn ngữ và đánh mất sự an tịnh của mình. Qua đó ông cho thấy sự bất lực của người Chăm là những người đã mất vinh quang xưa. Để cuối cùng ông rơi vào “thung lũng tình yêu”. Hãy để các nhà triết học tiếp tục cãi cọ, cuộc tranh luận không có kết thúc bởi tình yêu là thứ triết lý đơn thuần với cảm giác đang nắm trong tay công cụ nhị nguyên.

Rớt vào thung lũng tình yêu, thi sĩ đánh rơi thế giới và lạc mất chính mình. Tại đây xảy ra sự dịch chuyển đột ngột của sự kiện. Người đọc mong thi sĩ tìm thấy sự yên nghỉ trong tình yêu. Nhưng không. Thi sĩ tiếp tục đánh mất các vũ điệu dân tộc và các bài hát dân gian thuở xưa. Trái tim bị mù, ông như kẻ bị xa lánh rơi vào giữa một khu rừng trụi lá. Một thi ảnh tuyệt vời. Chúng ta có thể hình dung một người đàn ông trẻ tuyệt vọng rơi tõm vào giữa cánh rừng trơ trụi lá. Đây là đỉnh cao của một câu chuyện.

Ở phân đoạn thứ năm, thi sĩ cho biết khi đã đẩy vào cánh rừng trụi lá, ông buộc phải ngẩng đầu lên và bò ra. Sự thể găm vào tâm trí người đọchình ảnh một người lính bò ra khỏi rừng. Nhìn ở cấp độ vật lý là vậy, trên cấp độ tinh thần, thi sĩ cố vươn ra khỏi hố hang quá khứ. Ông như kẻ bị thương tìm lối ra khỏi đống đổ nát của thành phố tan hoang vì bom đạn. Có thể liên hệ hình ảnh này với dân tộc Chăm, cũng như kẻ từng mất bản sắc đang tìm lại mình. Hay về Việt Nam rũ bỏ tàn tích chiến tranh, trở lại nguyên vẹn là Việt Nam mạnh mẽ. Thi sĩ tái khám phá chính mình, hay tự mình khôi phục ánh sáng mặt trời của quê hương đã mất. Lòng yêu nước và tình yêu dân tộc và quê hương của ông cấu thành chính con người ông.

Như vậy, đây là một câu chuyện về thiên đường đã mất và tìm thấy lại. Thi sĩ lần nữa tìm thấy chính bản thân mình, ông là màu xanh lá. Niềm say mê cuộc sống làm đầy tràn ông. Thi sĩ lại xanh lá, dù rừng bị đốt cháy. Trong hồn ông, dòng sông chảy lại, dù sông đã qua đời. Hình ảnh này có thể nói về chiến tranh tàn phá Việt Nam nơi rừng và các con sông đã trở thành con mồi cho bom napalm. Cách khác, đây là chân dung của thế giới ngày nay, nơi đô thị hóa cướp đi đất rừng và nơi đập ngăn con sông lấy mất dòng chảy của chúng. Nhưng thi sĩ có cây xanh rực sáng trong ông. Dòng nước tình yêu trong trái tim ông không bị ngăn trở. Dân tộc ông như được sinh sôi. Sự biểu lộ tình cảm của thế giới nội tâm họ có thể mang thiên đường đã mất trở lại mặt đất. Thi sĩ trở thành một hoài niệm. Các bài hát ru chợt buồn. Tháp Chàm qua đó, đột nhiên hoang hóa trở lại. Tất cả trở lại bản thể uyên nguyên.

Người dân Việt Nam, đặc biệt là những người Chăm vốn theo đạothờ cúng tổ tiên. Bài thơ kết thúc với- giọng mẹ dịu êm ru ông vào giấc ngủ vĩnh hằng. Bài thơ hình như là một đối trọng với Kubla Khancủa Coleridge. Trong Kubla Khan, Coleridge nghe tiếng nói của tổ tiên dự tri chiến tranh. Còn ở đây, giọng nói xa vời của người mẹ giúp làm dịu tâm hồn thi sĩ, và ru ông vào một giấc ngủ vĩnh hằng. Tất cả những đam mê dành cho sự hiện hữu của một tâm trí tịnh an.

Trong chừng mực nào đó, bài thơ là nguyên mẫu mô tả quá trình của cuộc sống của con người trong bốn giai đoạn – thời thơ ấu,tuổi trẻ, thời thanh niên và tuổi già.