Inrasara: Memories of a Cham bard

Vietnam Heritage, 7-2011

I had to persuade him to recite onne more for me to record. He seemed lacking in enthusiasm. He was reluctant and forgot at many points. I understood. The chanted legends must be performed in a festival space, with its atmosphere

As a member of a Champa performing arts group, Mudwon Gru Han Phai – ‘Muwdon Gru’ is a priestly title – sang on prestigious platform in Saigon and performed at thousands of Cham festivals. He trained many Cham artists and was a live specimen for many researchers on the culture of Champa.

Mudwon Gru was also in the highest rank of priests of the middle religious sect, which synthesises Cam Ahier (Brahmanic or Hindu Champa) with Cam Awal (also called Cham Bani or Islamic Champa), overcoming conflict between these two religions.

A mudwon gru directs rites and festivities and is at the same time an all-round artist, singing, dancing and playing all kinds of traditional instruments from the ginơng, a pair of drums with one face of deerskin and the other of buffalo skin and beaten with sticks, and baranung, a single-faced drum beaten with the hands, to the xaranai, a wooden or ivory flute.

Mr Han Phai (as he can also be called) came from the village of My Nghiep, in the province of Ninh Thuan, in southern Central Vietnam, which is considered the most ancient Cham village, dating back more than a thousand years. He wandered among Cham villages playing a baranung and reciting epics. More than a dozen long, originally oral poems, eventually written down and kept in Cham villages, claim his authorship.

When I was a young man, I heard about the wandering bard Han Phai in all villages. During festivals, sometimes a week long, when the work in the fields and dinner were over, he led several disciples to my village in the twilight. Hundreds of people from surrounding villages gathered and waited for his chanting of the folklore of Champa.

With only a baranung, he sat on a reed mat in an open court and performed a poem to make us laugh, cry or become quiet. His invention, knowledge of tradition and echoing bass attracted rustic men and women, who could stay still daybreak.

I left my village to go to highschool in town, at the age of eleven. Three decades later memories of him seemed to vanish in my mind. Only when eventually I became a peasant again could I reach him. He was over seventy.

I rode my bicycle to his cultivated land “two cigarettes” from the village. He welcomed me with the same wrinkled eyes and sad smile. When I asked him about any record there might be of the legend he had chanted during the festivals, he said that nothing had been written down. Again a characteristic of Cham people: to want to live and leave no trace.

‘No need to write down. Thay are all in here,’ he said, poiting his finger to his left breast. I had to persuade him to recite once more for me to record. He seemed lacking in enthusiasm. He was reluctant and forgot at many points. I understood. The chanted legends must be performed in a festival space, with its atmosphere.

The epic is a particular genre of Cham folk performance. Even when they are written down, the chants are always reinvented by different mudwon gru and a mudwon gru sings different versions for different occasions. Numerous versions come into being.

‘Wait for me a little while,’ he said, and he brought a baranung from inside.

‘Now, we are off!’ Then he sang, with the rhythm of the beating of the drum.

In the old days the Kalong mountain was cold and silent

Today the mountain has Po Harim

In the old days, the Kalong land was sad and quiet

Today the land has the villages…

So great a talent, but, perhaps a decade after his death, when I found my way to his home, the family had kept nothing of his work. He was a player to the limit, then stopped. The poet wanted to leave the evanescence of his poetry.

Such great works are the condensation of the sacred spirit of heaven and earth, the Cham people think, so they are anonymous.

Note: Formed at the end of the second century of the common era and occupying the greater part of present Central Vietnam, the kingdom of Champa was gradually restricted southward and completely disappeared at the end of the 18th century. Presently, with a population of over 150,000, the Chams are living sporadically throughout Central and Southern Vietnam, in villages and hamlets. Their main occupations are farming, weaving, husbandry and pottery.

Classical Cham architecture and sculpture is among the world’s best. My Son, in Quang Nam province, is a World Heritage Site. The Chams practices Hinduism and Buddhism and then Islam. These three great religious traditions blended into a new faith called Cham Bani. The Cham people are matrilineal.

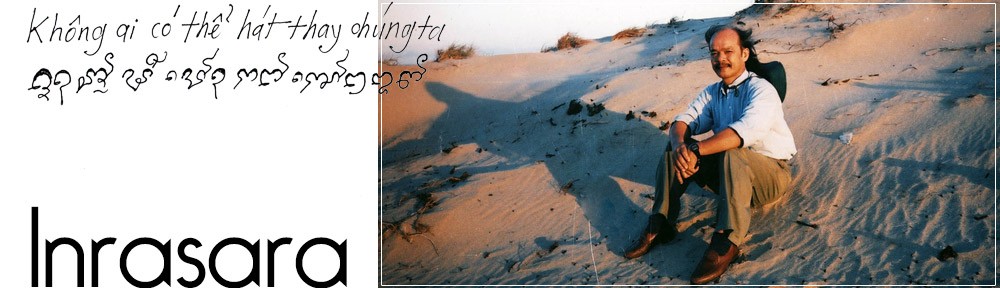

* Inrasara is a Cham Poet and well known expert on Cham culture.